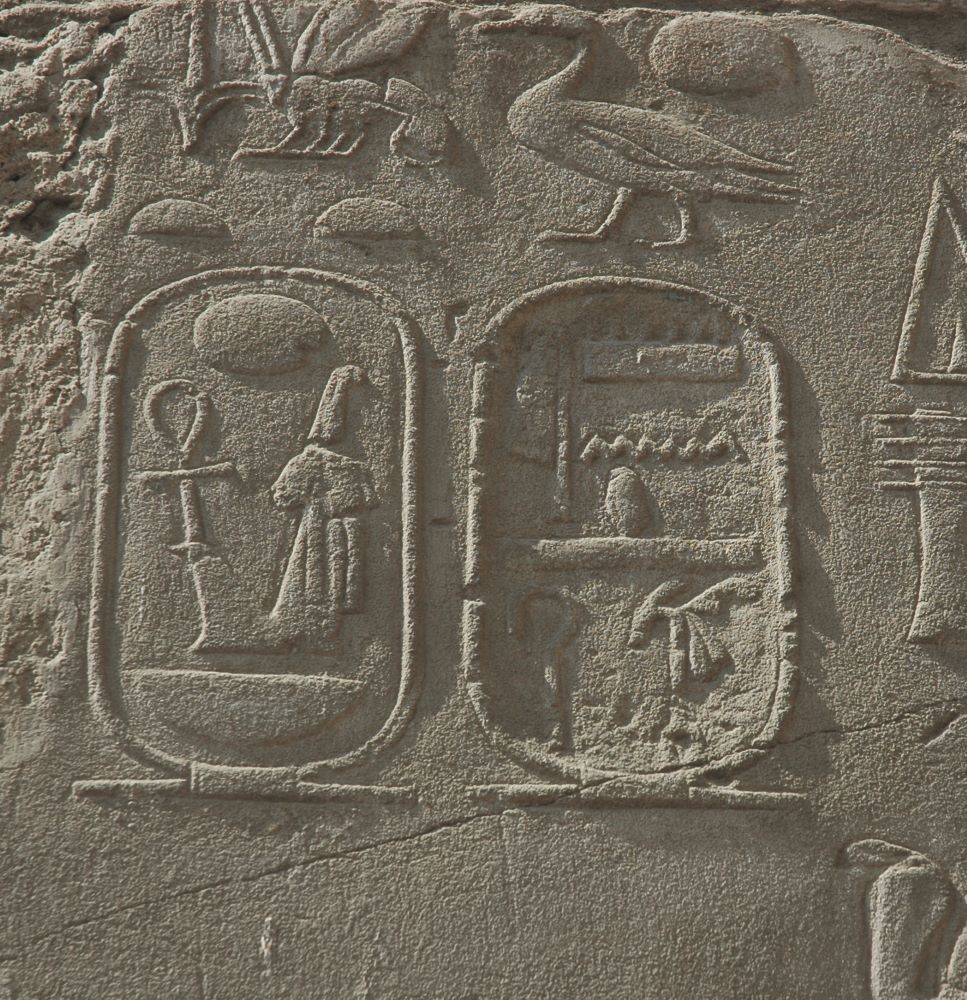

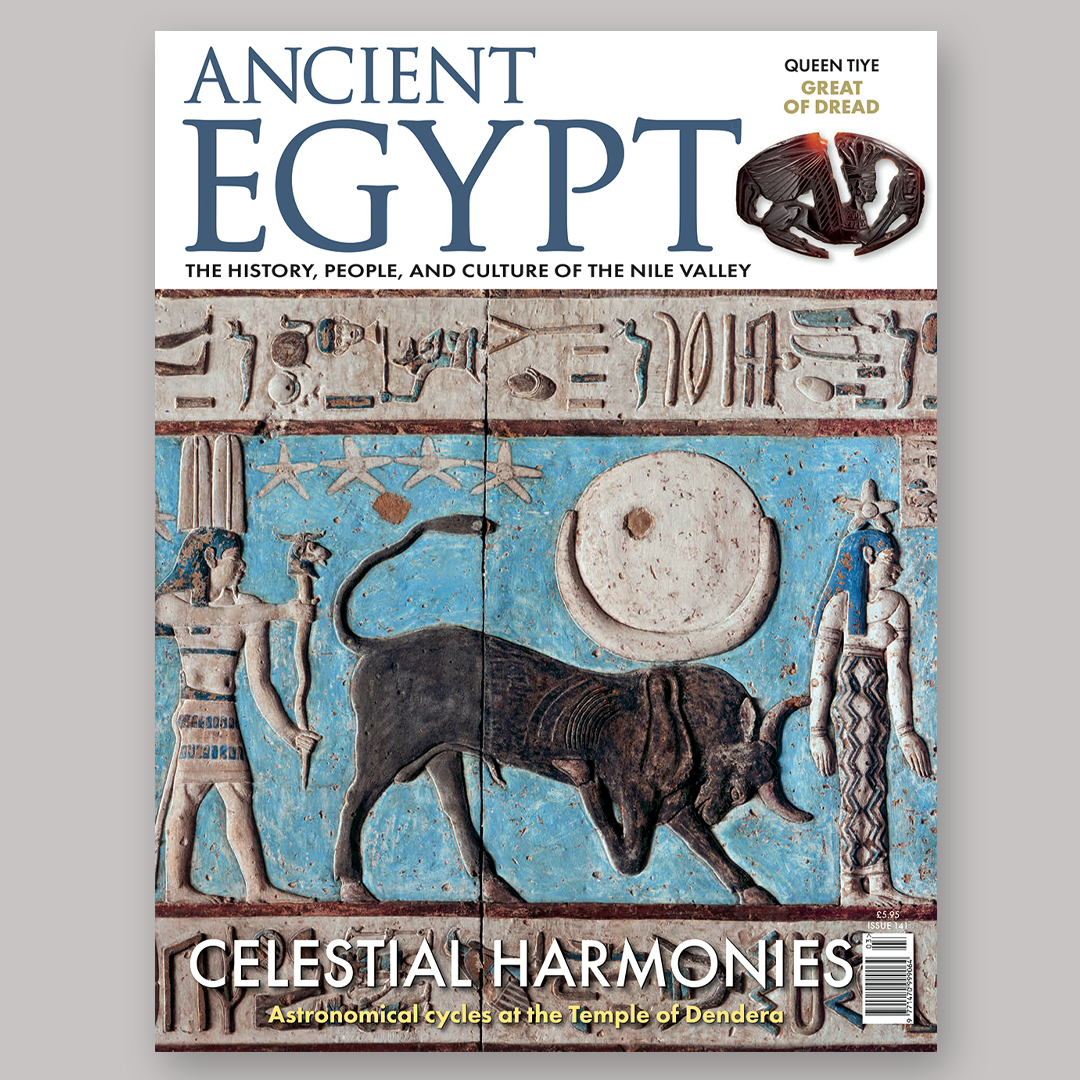

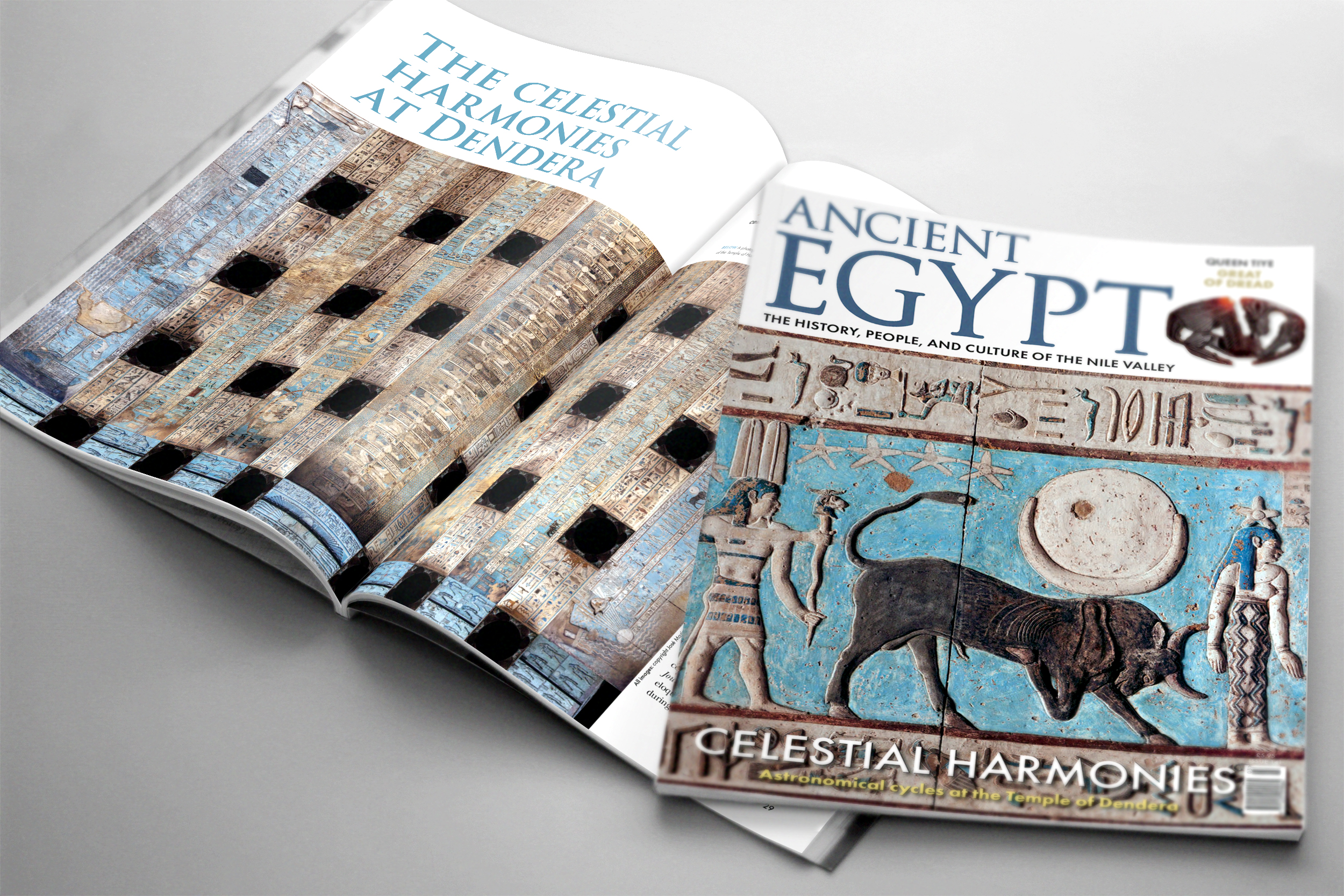

The Rectangular Zodiac

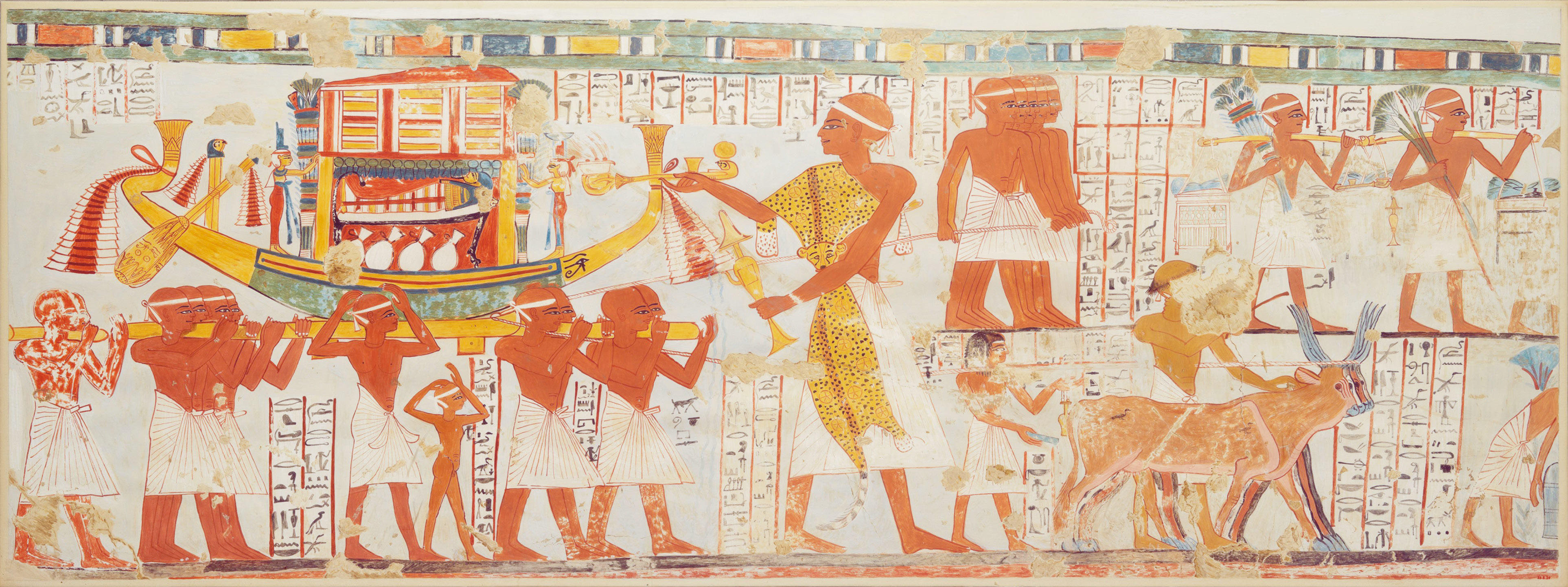

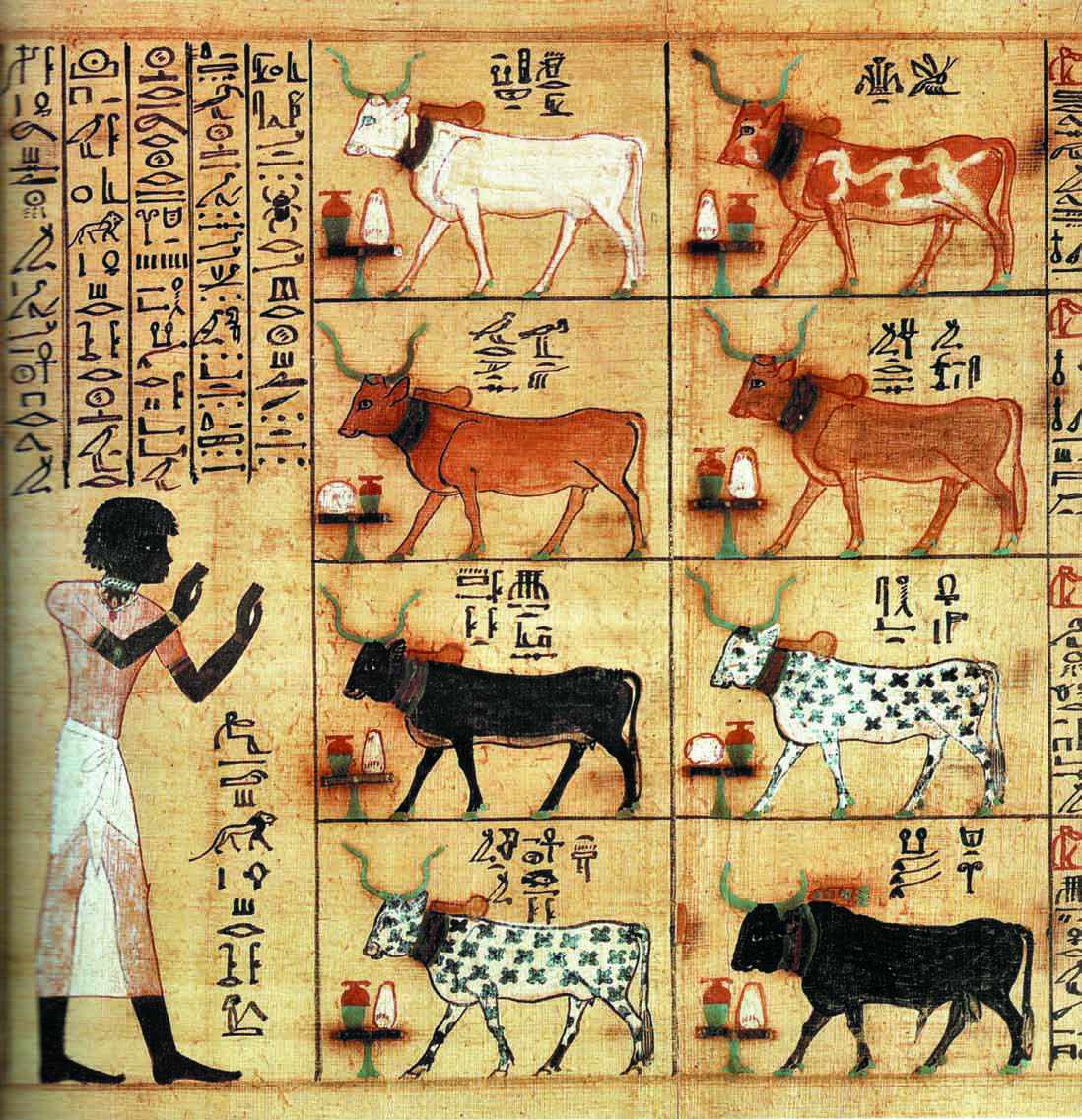

AE explores the beautifully restored ceiling of the pronaos of the Temple of Hathor at Dendera

All about Ancient Egypt

Welcome

Ancient Egypt magazine is now better than ever – a new design, created by a new team, but written by the familiar much-loved editors, has given the magazine a new, larger format, better to showcase the splendours of ancient Egypt.

About us

Ancient Egypt is the world's leading Egyptology magazine, exploring the history, people and culture of the Nile Valley. Now in a larger format with a fresh new design, AE brings you the latest news and discoveries, and feature articles covering more than 5000 years of Egyptian history.

Subscribe - and save up to 20%

Ancient Egypt is published bimonthly and available in print and digital formats. Subscribe and save up to 20% off the cover price, and you will receive your copies before they appear in the shops.

Digital Archive

Enjoy Ancient Egypt magazine wherever you are, home or away, with our digital subscription, with access to more than…